Review: The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes

Inevitably, when you’re reading a book like this biography once a week for only thirty minutes or so before you go to sleep, you’ll spend a lot of time flipping back through pages, trying to remember who’s who. After all, Conan Doyle knew a lot of people and once the famous author hits his stride, you realize he was friends, enemies and frenemies with a lot of other famous figures, including H.G. Wells, P.G. Wodehouse, Rudyard Kipling and Harry Houdini. He was related by marriage to E.W. Hornung, the creator of gentleman thief Arthur J. Raffles. He championed several causes, including overturning the wrongful conviction of two men, challenging England’s onerous divorce laws and, of course, spiritualism, which put him at odds with the church, skeptics and even other spiritualists.

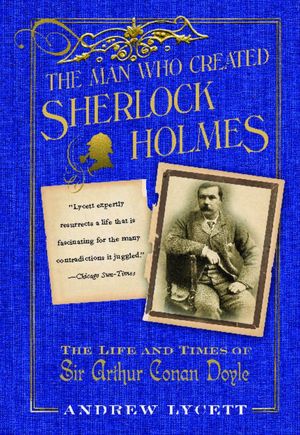

All this is as nothing compared to Conan Doyle’s greatest creation, that exemplar of cold logic and reasoning, Sherlock Holmes. Biographer Andrew Lycett, however, has done an admirable job of balancing the importance of Holmes, something Sir Arthur probably would have appreciated, but which might disappoint a Sherlockian. It’s easy to see, however, that the Canon represents only a small fraction of Conan Doyle’s output, despite how much Holmes looms large with the public.

The resulting portrait of Conan Doyle seemed quite understandable to me. I’d always wondered how someone who’d created the rational Holmes—“no ghosts need apply”—could be so gullible as to believe in faeries, automatic writing and ectoplasmic manifestations, but the deaths of so many so close to Conan Doyle (from disease and the Great War) and the burden left him by his creative but alcoholic, depressive and epileptic father, make his need to believe understandable. Conan Doyle was an outsize character who needed things to make sense, either by his own doing or by a power greater than himself. One of the byproducts of his own greatness was that singular creation, Sherlock Holmes.

Another byproduct of portraying this fascinating subject, coupled with the wealth of material Lycett was able to use following the deaths of several Doyle relations, is this somewhat daunting biography. It’s amazing how much we know about Conan Doyle, based on the many letters, journals and published works. Perhaps a less detailed biography would have made for easier reading, but even though I sometimes forgot who was who, I’m glad of Lycett’s thorough job.