Jane Austen: Self Publisher

During the whole truly annoying process of publishing my book, My Particular Friend, available wherever fine books are sold, it occurred to me that Jane Austen was also self published and that she faced many questions similar to those a modern day self publisher encounters.

During the whole truly annoying process of publishing my book, My Particular Friend, available wherever fine books are sold, it occurred to me that Jane Austen was also self published and that she faced many questions similar to those a modern day self publisher encounters.

Northanger Abbey

Of course she had already tried the first method when she sold in 1803 the copyright for Susan (which would eventually become Northanger Abbey) for £10 to Crosby & Co. They had confidently predicted an early publication, but they never published the novel, even after she had inquired in 1809 about its publication.

Her dealings with the publisher were admittedly complicated by the fact the copyright was sold to Crosby & Co. by the lawyer of her brother, Henry Austen, and the fact that she used a pseudonym, Mrs. Ashton Dennis, in communicating with the company. The pseudonym did allow her to use Mrs. Dennis’ initials in signing the letter (“I am Gentlemen &c &c MAD”), but it failed to provoke publication and so it wasn’t until the success of Sense and Sensibility, her first published novel, that she was able to raise the £10 needed to buy back the copyright. (The fact that S&S was published anonymously and that Austen employed a pseudonym in dealing with Crosby & Co. might have helped her buy back her copyright for the same price she sold it.)

Sense and Sensibility

When it came time to publish S&S in 1811, however, she chose not to sell the copyright (essentially relinquish all rights to it) and instead with the help of her brother Henry and the money of his wife (the Comtesse Eliza de Feuillide), published with Thomas Egerton’s company. In other words, Henry paid for it to be published hoping the sales would return a profit, which fortunately it did.

In 1813 however, she did sell the copyright for Pride and Prejudice to Egerton (he may have been more eager to buy after the success of S&S). Her decision was probably affected by Eliza’s illness (Eliza, like her mother, was dying of breast cancer). Publishing S&S was apparently a long process and she wanted to spare Henry such hands-on involvement for her second book. I take most of these speculations from Jon Spence’s Becoming Jane Austen.

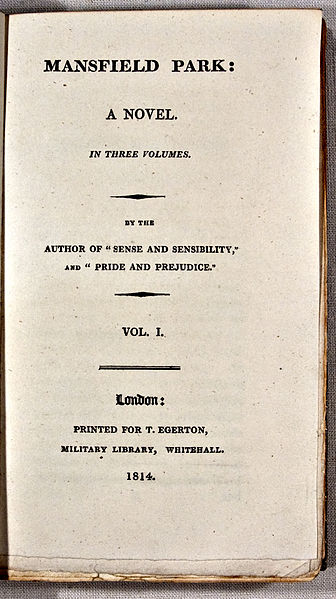

Mansfield Park

When it came time to publish Mansfield Park, however, Jane was looking at the £110 she got from Egerton for P&P and calculating how much he made from selling what was a fairly popular book. And to maximize profits, Egerton had printed P&P on the cheap.

So she decided to pay Egerton £250 to publish MP and probably told him to use thinner paper and print more lines per page to maximize her profits. These are the sort of calculations a self publisher has to make.

For instance, when I sell a book through CreateSpace (an Amazon company), I can elect to buy an ISBN (International Standard Book Number) for my book, which is important if I want to sell my book through distributors other than Amazon. For instance, if you go to your local bookstore in Poughkeepsie and ask about my book, they’ll say they don’t have it in stock, but if it has an ISBN, they can probably order it. Which really means that they’re ordering it obliquely through CreateSpace, which prints it on demand and ships it to the bookstore or directly to the customer.

But my royalties are pretty low when someone orders my book from a local bookstore (although I’m happy no matter how my book is bought), because everybody gets a cut. I end up with a $1.11 royalty on my $14 book. Now my royalties are tied to the number of pages of my book, so the fewer pages for the same price, the more my royalty.

Jane Austen today

I can just imagine Jane looking at Mansfield Park at a whopping 160,000 words (about twice the length of my book) in InDesign (she did S&S in Microsoft Word but wisely switched to InDesign for P&P). My Dover Thrift Edition of Mansfield Park, roughly 5.25×8.25 inches, runs to 322 pages. Were Jane to try to replicate this in InDesign, she’d be setting it at 10pt type (probably Times because it’s a pretty compact typeface and she might be worried about font embedding) over 11 pt leading, resulting in 43 lines of type per page. At least, that’s the typography of my Dover Thrift Edition.

My CreateSpace royalty calculator tell me that at $14 and 322 pages in length (which would mean no title page, preface, table of contents, etc.) at 5.5×8.5 inches (CreateSpace offers no 5.25×8.25 inch format), Jane would make a $3.69 royalty for each book sold through Amazon and an 89¢ royalty for each book sold through Barnes & Noble or independent bookstore.

According to The Cambridge Companion to Jane Austen, she and Egerton crammed 25 lines of type per page on three volumes for 1,008 pages in the original 1814 edition. Of course her considerations at that time were considerably different—she and Egerton were designing books to be read by candlelight or in a bumpy coach and without the benefit of high-index, antireflective reading glasses.

But were Jane self publishing today, she’d undoubtedly be making decision such as not forcing page breaks before chapters (there are 48 of them after all) and probably not sweating the widows and orphans—after all, with her long paragraphs, they weren’t much of a problem.

Now although today Jane could publish her book for no money upfront, she’d probably beg $25 from Henry for CreateSpace’s expanded distribution, which would allow independent bookstores and competitors to sell her book. And she’d wisely pay for an ISBN and create her own imprint rather than a free CreateSpace registered ISBN, because my own local bookstore, the Tattered Cover in Denver, won’t sell books solely distributed by Amazon (er, CreateSpace). By paying for my ISBN and creating my own imprint, however, the TC is happy to sell my book.

ISBNs

Now Jane could opt for either buying for $125 a single ISBN from Bowker, the company that sells ISBNs in the U.S.—we’re imagining Jane now lives in the United States (actually, CreateSpace only distributes in the U.S.). Or a block of 10 for $250. Or, she could buy a $10 ISBN from CreateSpace, which I was what I did, thinking that a better deal. CreateSpace can obviously negotiate a good deal from Bowker for buying ISBNs in bulk.

But what might surprise Jane later on is when she prepares her EBOOK version of Mansfield Park, because you’re actually supposed to get a separate ISBN for each format of your book: the audio book, the large print edition (we Janeites are generally an older crowd), the annotated edition, etc. Now Jane is regretting her decision to go with the $10 CreateSpace ISBN. She should have asked her husband … I mean her brother … to buy that block of 10 from Bowker.

Copyright

Of course, Jane might also decide she should get a copyright for her book. Fortunately it only costs $35 to register electronically with the U.S. Copyright Office and she can upload the PDF of her book from her Mac (being a woman of sense, she is of the cult of Mac).

LCCN

Then she gets another rude surprise. Jane is interested in reaching a wider audience and decides she must obtain a Library of Congress Control Number because without that number, local libraries can’t catalog her book. Unfortunately she learns from the Library of Congress that they don’t catalog self-published works.

She realizes she has two options: she could either submit her work through her fictitious imprint, lets call it Chawton Press, or she could create a new edition of her book through CreateSpace and opt for a free CreateSpace assigned and registered ISBN. That is, CreateSpace is registered as the publisher and will register your book with the LOC.

My impression of Jane, from reading various biographies, is that she would probably enjoy being a self published author. She wouldn’t need to deal with literary agents (they didn’t exist in the Regency), she could spell “friend” anyway she liked and wouldn’t have to listen to anyone telling her 160,000 words might be a little long for a novel. And Chawton Press would make a darn nice imprint.