His Last Bow quiz

Certain things you leave till last. I’ve never read Agatha Christie’s Curtains, for instance, or the director’s cut of Blade Runner and for years I’ve put off re-reading Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s His Last Bow. (I had read it so many years ago that it’s but a dim memory, but since then, I’ve avoided it.)

Certain things you leave till last. I’ve never read Agatha Christie’s Curtains, for instance, or the director’s cut of Blade Runner and for years I’ve put off re-reading Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s His Last Bow. (I had read it so many years ago that it’s but a dim memory, but since then, I’ve avoided it.)

It isn’t as if the Great Detective Sherlock Holmes or his biographer Dr. John H. Watson die in the story, of course, but it still has a palpable sense of melancholy that I distantly remember from that long ago first reading.

What possessed me, therefore, to suggest it as the next story for my Holmes scion group to discuss, I do not know. I had won the trivia quiz at the meeting of Doctor Watson’s Neglected Patients for my knowledge of The Stockbroker’s Clerk and had the honor of choosing the next story. I suppose my surprise at winning is responsible for my hasty decision.

It’s a hard story to make a quiz from because it’s relatively short—about 6,100 words—and its structure does not lend itself to details. It has, of course, one of the best lines in the Canon, possibly reveals the first name of Mrs. Hudson and gives us the title of Holmes’ magnum opus. The story is also peculiar in being told in third person (a peculiarity shared with The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone).

The story is set at the beginning of the First World War. In fact it must be the most precisely dated story in the Canon, for it begins: “It was nine o’clock at night upon the second of August—the most terrible August in the history of the world.” The location is not so clearly labeled, but it is on the English coast overlooking a bay (a mention of chalk cliffs inevitably means Dover, but there’s also mention of Harwick, to the north of the Thames estuary). Two men—a Baron Von Herling, chief secretary to the German legation (a German diplomatic mission just below the status of an embassy) and Von Bork, a not so secret agent—are discussing the latter’s imminent departure from England. Von Bork only awaits a last treasure trove of secrets—British naval signals—that will shortly be delivered to him by Altamont, an Irish-American informant. Von Bork tells Von Herling:

I grudge Altamont nothing. He is a wonderful worker. If I pay him well, at least he delivers the goods, to use his own phrase. Besides he is not a traitor. I assure you that our most pan-Germanic Junker is a sucking dove in his feelings towards England as compared with a real bitter Irish-American.”

Altamont, however, is none other than Holmes, who has been working to subvert the efforts of Von Bork. The German has been openly living in England for the past four years, living the sporting life, and has secretly been gathering intelligence for Germany. Holmes tells Watson (who acted as Altamont’s chauffeur) at the end of the affair:

[Von Bork] was in a class by himself. Things were going wrong, and no one could understand why they were going wrong. Agents were suspected or even caught, but there was evidence of some strong and secret central force. It was absolutely necessary to expose it. Strong pressure [the prime minister] was brought upon me to look into the matter.”

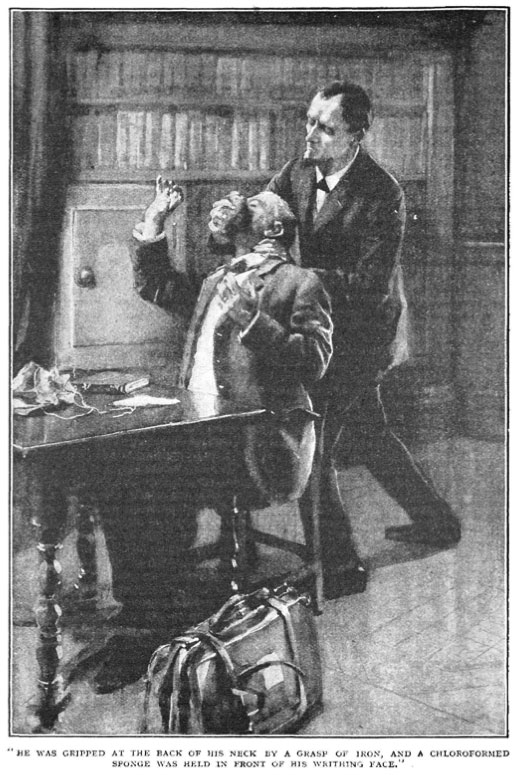

After Von Bork tells Altamont of his cunning plans (and obligingly opens his safe), Holmes springs his trap, subduing the spymaster with a chloroform-soaked sponge. He calls Watson to help him gather up the intelligence Von Bork has collected and also place the struggling agent in their car for transport back to London. At the very end of the story is this exchange:

There’s an east wind coming, Watson.”

“I think not, Holmes. It is very warm.”

“Good old Watson! You are the one fixed point in a changing age. There’s an east wind coming all the same, such a wind as never blew on England yet. It will be cold and bitter, Watson, and a good many of us may wither before its blast. But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.”

It’s hard for a modern reader to share Holmes’ optimism, considering the death toll of the Great War and the inevitability of the Second World War, but his affection for Watson still comes through. It seems a fitting end to the tales of Holmes and Watson, although of course there were more stories Doyle published after the collection also called His Last Bow. But this story is the last story chronologically and in my youth, I felt the shades close around the 60-year-old detective. With my sixties in the offing, however, perhaps I’m willing to concede Holmes has many more untold adventures left.

I may also be receptive to visiting the story because of Laurie King’s Mary Russell series. I’m just now reading Garment of Shadows, set long after the First World War, with a Holmes about seventy and his bride in her twenties (forgive me if I have Russell’s age incorrect). I’m also reading a biography of Doyle where the war is just about to start. And also reading Her Majesty’s Secret Service by Christopher Andrew, where again the war is about to start. And my own book, Jane, Actually, has a character who says he died during the Battle of the Somme. So perhaps my choice is not so surprising after all.

Reading Her Majesty’s Secret Service, I’m struck by the general spy hysteria in the pre-war era, by the actual bizarre and often comical nature of British and German spies and by the resonance in the story to other spy stories of the era, particularly The Riddle of the Sands.

After finally re-reading the story after all this time, I find the actual adventure to be non-existent: it’s essentially talking heads, either Von Bork congratulating himself on his spying or Holmes congratulating himself on his capture of Von Bork. There is no chase across the moors or examples of Holmes’ deductive skills (“You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive”) or consulting of railway time tables. Nevertheless, the story is pregnant with significance to a modern reader. It was published in 1917, with a year of fighting ahead. Doyle was in his fifties writing about his aging detective. Holmes words at the end can only be construed as a patriotic appeal by Doyle to the public, not to give up hope.

The story’s sense of melancholy is further heightened as Holmes mentions several of his most famous adversaries. You just get the sense this was one last adventure for Holmes and Watson.

But perhaps I can take comfort in the exploits of those aging cinematic heroes Bruce Willis and Sylvester Stallone and Harrison Ford. Holmes may be exclaiming “the game’s afoot” well into his eighties.

There are a host of resources attendant to this story. You can read it at Project Gutenberg and wikisource or listen to it at Librivox. There’s a nice examination of the story at what I suspect is a now abandoned web project at Stanford. A nice little feature at the Stanford site allows you to download the story as it appeared in The Strand Magazine. And, of course, the last lines of the story are also used in the 1942 Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror, starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Holmes and Watson. Again, Holmes’ speech can be heard as a patriotic appeal to his countrymen.

Now back to the quiz. The Outpatients of DWNP meet at 12:30 p.m. this Sunday, April 4, at Pints Pub as usual. Outpatients, understandably, should not read the quiz in advance. I won’t supply the answers until after the meeting. The last question is meant to be a tie breaker. Not counting the tie-breaker, there are a possible 30 points.