The Adventure of the Second Stain

Oh what a wonderful story for those who love to nitpick. It has so many nuggets that one can brood over on a long winter night—and one giant elephant in the room so obvious that it makes one want to re-evaluate the vaunted intellect of the great detective Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Oh what a wonderful story for those who love to nitpick. It has so many nuggets that one can brood over on a long winter night—and one giant elephant in the room so obvious that it makes one want to re-evaluate the vaunted intellect of the great detective Mr. Sherlock Holmes.

Here’s a not too brief summary of The Adventure of the Second Stain (along with the usual River Song warning “Spoilers!”): The Secretary for European Affairs Mr. Trelawney Hope has lost a letter sent to the crown by a foreign potentate. The contents of the letter are so explosive that should it be widely known, it would lead to war, even though the potentate has since regretted sending it. Hope has brought the letter home with him each night, keeping it in a locked despatch-box in his bedroom, but overnight it has vanished, and neither Hope nor his wife have an explanation. They trust the servants and all swear no entered the room. Hope also says no one in the household save he would know that the despatch-box contained such an important letter.

Holmes takes the case and tells his biographer Dr. John Watson that one of three foreign agents might be responsible, one of whom is Eduardo Lucas. Watson surprises Holmes by telling him that Lucas is dead, as he has just read in the newspaper. It appears that Lucas’ valet had found his master stabbed dead just the previous night. Immediately after this news, Holmes and Watson are interrupted by the arrival of Lady Trelawney Hope, who asks whether Holmes can divulge the exact nature of the disaster that has befallen her husband. She only knows that a valuable paper has gone missing.

Holmes tells her that if her husband has not taken her into his confidence, then Holmes cannot presume to do so. She implores Holmes, saying “Let no regard for your client’s interests keep you silent, for I assure you that his interests, if he would only see it, would be best served by taking me into his complete confidence.” But Holmes is adamant and she leaves after asking that her visit to Holmes remains a secret.

For the next several days, Holmes “ran out and ran in, smoked incessantly, played snatches on his violin, sank into reveries, devoured sandwiches at irregular hours, and hardly answered the casual questions which I put to him. It was evident to me that things were not going well with him or his quest.” During the period, Lucas’ valet is arrested and then released after his alibi is confirmed.

On the fourth day (I am unsure if this is the fourth day after Holmes is contacted or the fourth day after the murder and theft of the letter), the newspapers report that Eduardo Lucas has led a dual existence as M. Henri Fournaye, living in Paris with his wife—“reported to the authorities by her servants as being insane.” Mme. Fournaye is suspected of having followed Lucas back to London and killed him in an insane rage. “At present she is unable to give any coherent account of the past, and the doctors hold out no hopes of the reestablishment of her reason.”

Immediately upon reading this, Holmes receives a note from Inspector Lestrade summoning him to Lucas’ house. Lestrade confirms the newspaper report and declares the murder solved, but tells him that they have noted a trifling discrepancy that he thought would interest Holmes. Upon considering the case closed, the police obligingly thought they should tidy up a bit and had occasion to raise the carpet upon which the dead man had been found. Not too surprisingly, there was a large blood stain upon the carpet, but no corresponding blood stain on the white woodwork underneath, even though Lucas had bled profusely.

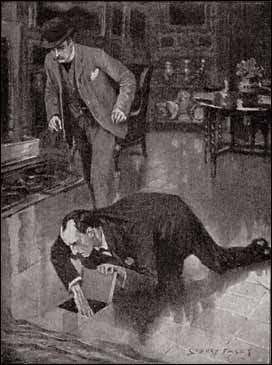

However there is another bloodstain on another part of the floor. Obviously the “carpet has been turned round,” but by whom, Lestrade asks? Holmes then requests that Lestrade question the constable who had been guarding the crime scene, explaining that the constable must have allowed someone to enter who had moved the carpet. While Lestrade attends to this, Holmes springs into action, pulling aside the carpet and searches the floor for a hidden compartment. He finds a loose board and searches the cavity underneath but fails to find the letter.

Lestrade returns with the constable, who confesses that a handsome, “well-grown young woman” had asked to see the crime scene, but upon seeing the blood stain, the woman had fainted. The constable had left her to fetch some brandy to revive her, but upon returning, saw that the woman had fled.

Holmes abruptly declares “Come, Watson, I think that we have more important work elsewhere,” and leaves, but first shows the constable a photograph. The constable then cries, “Good Lord, sir!” Once outside, Holmes tells Watson: “You will be relieved to hear that there will be no war, that the Right Honourable Trelawney Hope will suffer no setback in his brilliant career, that the indiscreet Sovereign will receive no punishment for his indiscretion, that the Prime Minister will have no European complication to deal with, and that with a little tact and management upon our part nobody will be a penny the worse for what might have been a very ugly incident.”

Holmes and Watson then pay a visit to Lady Hilda, whereupon Holmes accuses her of the theft of the letter. She feigns innocence, but he threatens to tell her husband, who is due to arrive home at any minute, of his suspicions. She finally admits that Lucas had blackmailed her with an indiscreet letter she had written before her marriage. Lucas demands she steal the letter and provides her a duplicate key to the despatch-box, a key made from a wax impression Lady Hilda had taken of the original.

She took the letter to Lucas at his home, only to be interrupted in the exchange by Lucas’ enraged wife: “My waiting is not in vain. At last, at last I have found you with her!” Lady Hilda flees before the murder is committed and only learns of the outcome the next day. Once she realizes how devastated her husband is by the loss of the letter, she determines to gain entrance to Lucas’ house and retrieve the letter from the hiding spot.

Satisfied by the explanation, Holmes uses the duplicate key to hide the letter in the despatch-box, still in the couple’s bedroom. When Hope and the prime minister arrive, Holmes urges Hope to look again in the box, giving his reasoning that since the letter has not been used, it must still remain in the box. Despite his pessimism, Hope searches, finds the letter mixed in with other documents, and is overjoyed to find it. His happiness knows no bounds, which may explain his wholesale acceptance of the fact that the letter was merely mislaid. The prime minister, however, suspects “there is more in this than meets the eye,” but Holmes responds: “We also have our diplomatic secrets.”

It is, of course, a trifle, but there is nothing so important as trifles.

The prime minister certainly knows what he’s talking about. There are several points of interest in this story that Holmes does not address. They are admittedly trifles, but as Holmes has observed, much can be made of trifles. Lady Hilda tells Holmes that upon the sound of Mme. Fournaye at the door (when she handed the letter to Lucas), “Lucas quickly turned back the drugget [carpet], thrust the document into some hiding-place there, and covered it over.” This indicates that Lady Hilda knew the location of the hiding-place. Why then would she turn the carpet round? If you look for something under a carpet, you pull it back, you don’t turn it round.

Another trifle: Hope told Holmes: “Besides the members of the Cabinet there are two, or possibly three, departmental officials who know of the letter. No one else in England, Mr. Holmes, I assure you.” And yet Lady Hilda tells Holmes: “He [Lucas] said that he would return my letter if I would bring him a certain document which he described in my husband’s despatch-box. He had some spy in the office who had told him of its existence.” Very obviously Lucas knew of the letter and its importance and that Hope brought the letter home in the despatch-box. I certainly hope at some point that Holmes warns the prime minister that his ship of state is leaking from the top.

I won’t go into the stupidity of Hope bringing the letter home, rather than entrusting it to the security of a safe in Whitehall, but I strongly suspect that some member of the government wanted the letter to be made public.

But now onto the item that is not trifling—in fact it is so monstrous an instance of oversight that my estimation of Holmes has fallen. Watson says of his visit to Lucas’ home—“It was my first visit to the scene of the crime”—but events show that it is also Holmes’ first visit to the house.

Now in many stories, Holmes has shown a reluctance to visit a person or location that others consider pertinent, but to have not visited the crime scene of a suspected spy who dies the day after the theft of an important paper is an almost criminal lapse. Holmes depends on Lestrade to tell him that the blood stain does not correspond with the corresponding stain upon the floor.

We are left with only a few explanations: Holmes never visited the crime scene; Holmes has visited the crime scene, failed to notice the discrepancy and Watson has neglected to tell us of the visit; or Holmes visited the crime scene before Lady Hilda turned round the carpet, failed to find the letter and again Watson has failed to inform us of this visit. Only the last explanation redeems Holmes in any way, although it still puts his observational skills in doubt if he fails to find a hidden compartment almost directly under where the body was found.

Notes of interest

Now please don’t think my harsh observations indicate any disliking of the story. I positively delight in finding gaps in logic in the Canon; it stimulates the little gray cells. And this story has so many brilliant touches. It has the wonderful observation by Holmes: “ ‘Now, Watson, the fair sex is your department,’ said Holmes, with a smile, when the dwindling frou-frou of skirts had ended in the slam of the front door.”

Then there is the whole matter of whether this Second Stain is the Second Stain mentioned in the Naval Treaty or whether there is in fact another unpublished account involving a different second stain. And I also enjoyed the evolution of Holmes’ relationship with Lestrade. He is no longer the “little sallow rat-faced, dark-eyed fellow” in A Study in Scarlet or the “lean, ferret-like man, furtive and sly-looking,” in The Boscombe Valley Mystery. Instead, says Watson, Lestrade’s “bulldog features gazed out at us from the front window, and he greeted us warmly.”

All in all, a very entertaining adventure and so pleasing to realize that after having read these stories so many times, I can still find trifles that amuse.