A Scandal in Bohemia uncovered

I read, but I did not comprehend. That was obvious when fellow Sherlockian Mike Newman asked this quiz question at the July meeting of Doctor Watson’s Neglected Patients: “What are the first two sentences of A Scandal in Bohemia?” He even gave the hint that the first sentence begins “To Sherlock Holmes …”

I read, but I did not comprehend. That was obvious when fellow Sherlockian Mike Newman asked this quiz question at the July meeting of Doctor Watson’s Neglected Patients: “What are the first two sentences of A Scandal in Bohemia?” He even gave the hint that the first sentence begins “To Sherlock Holmes …”

To say that I felt like a complete idiot would be an understatement. I’ve read this story countless times. It’s one of the most popular stories in the Canon. I dearly wanted to win this quiz and remembered the fact that seventeen steps led from the hall to the sitting room of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson, that a cabinet photo is a four by six and that Count von Kramm (aka the King of Bohemia, which technically did not exist as a recognized political entity) had five times had his agents attempt to recover the incriminating photograph from the American adventuress Irene Adler, twice by burglary, once by diverting her luggage and twice by waylaying her and presumably searching her.

But what I did not really do is read it. I analyzed and dissected it, but I did not really read it for the very entertaining story that it is. Or else I should have remembered these lines: “To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name.”

[audio http://ia700501.us.archive.org/2/items/adventures_sherlock_holmes_rg_librivox/adventuresholmes_01_doyle.mp3]Ah well, at least I am able to easily recall the facts of the case: on the 20th of March 1888, Watson, now married to Mary Morstan after the incidents he recorded in The Sign of Four, decides to pay his old friend a visit, just before Holmes is also visited by the somewhat comic opera figure wearing a mask and calling himself Count von Kramm.

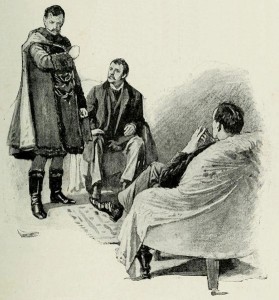

Holmes identifies his guest as the king, who acknowledges his identify and then explains his problem. He is to marry the second daughter of the king of Scandinavia, and she won’t look kindly on the king’s youthful dalliances, captured by a photograph in the possession of Miss Adler. He asks Holmes to retrieve the photograph and advances him three hundred pounds in gold and seven hundred in notes.

The next day, Holmes adopts the disguise of a groom (an itinerant stablehand in this case) and follows Adler and a man to the Church of St. Monica in the Edgeware Road. Through a bizarre circumstance, Holmes is asked to be a witness to the wedding of Adler and Mr. Godfrey Norton and is paid a sovereign, which Holmes proposes to keep on his watch chain as a souvenir.

The discovery that Adler is now Mrs. Godfrey Norton throws a different light on the matter, Holmes informs Watson. He surmises that her marriage will probably make Madame Norton as averse to seeing the photograph made public as the king. Holmes then explains to Watson his scheme to uncover where the former Miss Adler has hidden the photo and enlists Watson’s aid.

Holmes’ scheme is worthy of an episode of Hustle: he’s enlisted a street troupe of guardsmen, toffs, loafers, a nurse and a scissors grinder to greet the adventuress (I dearly want to be an adventuress) when she returns home. A scuffle ensues when the loafers fight to have the honor of (and get a tip for) opening the door of her carriage. Holmes, who is standing nearby in the disguise of a simple-minded Nonconformist minister, is struck down in the confusion.

Mrs. Norton invites the stricken minister inside and attends to his wounds. At a signal from Holmes, Watson, who was part of the crowd and has been lurking outside, tosses a plumber’s smoke rocket into Mrs. Norton’s cottage and raises the cry of “Fire!” Mrs. Norton betrays the location of the photograph, which Holmes observes.

“The photograph is in a recess behind a sliding panel just above the right bell-pull. She was there in an instant, and I caught a glimpse of it as she half drew it out. When I cried out that it was a false alarm, she replaced it, glanced at the rocket, rushed from the room, and I have not seen her since. I rose, and, making my excuses, escaped from the house. I hesitated whether to attempt to secure the photograph at once; but the coachman had come in, and as he was watching me narrowly, it seemed safer to wait. A little over-precipitance may ruin all.”

Holmes and Watson return to Baker Street and as he searches for his keys, Holmes is greeted by a slight young man who says, “Good-night, Mister Sherlock Holmes.”

The next morning, the king arrives and with Holmes and Watson they leave for Mrs. Norton’s cottage, but they find the adventuress is gone. Holmes rushes for the sliding panel and finds a letter addressed to Holmes:

“MY DEAR MR. SHERLOCK HOLMES,—You really did it very well. You took me in completely. Until after the alarm of fire, I had not a suspicion. But then, when I found how I had betrayed myself, I began to think. I had been warned against you months ago. I had been told that, if the King employed an agent, it would certainly be you. And your address had been given me. Yet, with all this, you made me reveal what you wanted to know. Even after I became suspicious, I found it hard to think evil of such a dear, kind old clergyman. But, you know, I have been trained as an actress myself. Male costume is nothing new to me. I often take advantage of the freedom which it gives. I sent John, the coachman, to watch you, ran upstairs, got into my walking clothes, as I call them, and came down just as you departed.”

She also tells Holmes to inform the king that she will keep the incriminating photograph of herself and the king but only for protection. She leaves a photograph of herself for the king as consolation, who cries out:

“What a woman—oh, what a woman!” cried the King of Bohemia, when we had all three read this epistle. “Did I not tell you how quick and resolute she was? Would she not have made an admirable queen? Is it not a pity that she was not on my level?”

“From what I have seen of the lady, she seems, indeed, to be on a very different level to your Majesty,” said Holmes coldly. “I am sorry that I have not been able to bring your Majesty’s business to a more successful conclusion.”

“On the contrary, my dear sir,” cried the King; “nothing could be more successful. I know that her word is inviolate. The photograph is now as safe as if it were in the fire.”

The king tries to reward Holmes with an emerald snake ring but Holmes asks for only the photograph.

And that was how a great scandal threatened to affect the kingdom of Bohemia, and how the best plans of Mr. Sherlock Holmes were beaten by a woman’s wit. He used to make merry over the cleverness of women, but I have not heard him do it of late. And when he speaks of Irene Adler, or when he refers to her photograph, it is always under the honourable title of thewoman.

It’s a classic story and the first of the serialized short stories that, far more than the previously published A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four, catapulted Holmes, Watson and Doyle to fame. It has a number of firsts: the first time that Holmes’ misogyny is codified; the first recorded case that Holmes lost; and to my knowledge, the only time Holmes asks for expenses. It may very well be one of his most lucrative recorded cases (in The Adventure of the Priory School he pockets £6,000). Although he refused the king’s ring, he still had the £1,000 in expenses (plumber’s rockets and paying the crowd outside Adler’s cottage couldn’t have amounted to much) and later in A Case of Identity, we learn the king has sent Holmes a gold snuff box with embedded amethyst as extra compensation.

Despite SCAN being a wonderful story, however, I do have one very large qualm about it. It seems to me that the whole contretemps is somewhat manufactured by both the king and Adler. Consider … the king tells Holmes his agents have tried five times to retrieve the letter and he tell Holmes that Adler has threatened that “she would send it on the day when the betrothal was publicly proclaimed. That will be next Monday.”

But why would Adler make public the photograph if, as Holmes believes, she would not want her future husband to know about her affair with the king? And why not simply give the king the photo if she was not planning to blackmail him? In her letter to Holmes, she says: “The King may do what he will without hindrance from one whom he has cruelly wronged. I keep it only to safeguard myself, and to preserve a weapon which will always secure me from any steps which he might take in the future.”

So in other words, if Adler had given the king the photo, which she hadn’t planned to use against him, the king wouldn’t have needed to send his agents to get the photo. If he hadn’t sent his agents, she wouldn’t have needed to threaten to make the photo public.

The conclusion of the story is also baffling. Although Holmes bungled the case and allowed Adler to escape with the photo, the king is satisfied with her promise not to make the photo public: “I know that her word is inviolate. The photograph is now as safe as if it were in the fire.”

I do not see that circumstances have changed materially, and yet the king is satisfied. Why couldn’t Adler have told him from the beginning that she was not planning to use the photo against him but would retain ownership? I cannot help but be baffled. Holmes has done nothing but is richly rewarded.

I am also baffled by Holmes’ strategy to get Adler to reveal the hiding place of the photo. Once it was revealed that the fire was a ploy, he should have immediately obtained the photo or he should have remained with Adler in the guise of the clergyman. “A little over-precipitance may ruin all,” he told Watson. Waiting until the next morning, however, all but ensured she would escape.

Unless, of course, that was Holmes’ plan. Might he have had sympathy for Adler’s plight? I would rather believe that than think how badly he planned the thing.

Quibbles aside, A Scandal in Bohemia is truly one of the best stories in the Canon and has inspired pastiche authors from Carole Nelson Douglas and her Irene Adler series and Amy Thomas and her Adler series. And the character has been handled so differently from the BBC Sherlock to the CBS Elementary.

So how did I do on the quiz? Out of 17 questions and 30 possible points, I scored 23, but Mark Langston scored 25, curse him. My only consolation is that he too failed on the first two sentences question. We both remembered the first sentence (although it took me an embarrassingly long time), but he confused the third sentence (“In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex”) with the second.

The next meeting of DWNP is at 12:30 p.m. Aug. 4 at Pints Pub. The story to be discussed is The Boscombe Valley Mystery.

PS An observation about currency in this story: there’s a lot of it, from the twopence (pronounced “tuppence”; pre-decimalization, a pound equaled 240 pence) that Holmes’ drunken groom character receives for rubbing down the horses in the nearby mews (stables) to Briony Lodge, Adler’s home; to the half a crown (a crown is five shilling;s) price of the princely pink paper on which Count von Kramm sent his note to Holmes; to the half a guinea (there are 20 shillings to the pound and a guinea is 21 shillings) Mr. Norton promises if his coachmen gets him to the church on time; to the half a sovereign both Adler and Holmes promises their cabbies; to the sovereign (another name for a pound) that Mrs. Norton gives to Holmes as payment for being a witness to her wedding.

Incidentally, the historical currency converter at the National Archives estimates that the £1,000 Holmes gets as expenses (and as far as I can tell from the story, Holmes keeps), would be worth £59,890 in 2005, which my computer’s currency converter puts at $92,085.

Another synonym for pound is quid. A sovereign is a gold coin.