The Adventure of the Lion’s Mane, not a favorite

I’m a person who pours alcohol on wounds, scratches mosquito bites until they bleed and picks at scabs. In other words, I’m obsessed about things I don’t particularly like and that must account for the reason that I suggested that Doctor Watson’s Neglected Patients should next discuss this story at our monthly Outpatients Meeting.

I dislike this story for many reasons, but the most obvious to even the most casual Sherlockian is that it Doctor John H. Watson, Sherlock Holmes’ biographer, does not play a part in the narrative. In fact the story is narrated by Holmes, who is in retirement on the Sussex Downs, keeping bees.

And that retirement bit also rankles me. I fail to understand how Holmes could have so willingly given up the hustle and bustle and crime of London for the quiet life of the country, where his only decision on a day-to-day basis is whether to shave or not. This is a man who lived for the observation of trifles, who required cocaine lest his mind stagnate, and yet in his old age is content to rusticate amid the bees and flower. I just don’t buy it, possibly because I am now older than Holmes was when this story takes place.* I don’t like the idea that I may suddenly turn my back on all those things that have given me pleasure over the years, like Star Trek, P.G. Wodehouse, aikido and Sherlock Holmes.

I also hate the idea that Watson and Holmes have grown apart: “At this period of my life the good Watson had passed almost beyond my ken. An occasional week-end visit was the most that I ever saw of him.” Unfortunately, that seems more credible than the idea that Holmes could give up London; we’ve all left friends behind when we leave town—friends we mean to stay in touch with but inexplicably drift apart from. It’s a sad thought.

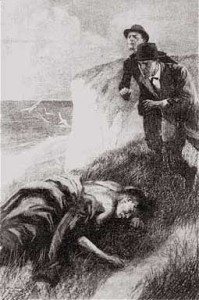

But beyond all this, there’s something about this story that I find so infuriating it colors my entire judgment of the story. I’ll refrain from mentioning it until the end of this analysis, however. First to the facts of the case: Holmes is retired with only his housekeeper for company (never said to be Mrs. Hudson) and his only close acquaintance is Harold Stackhurst, who runs a nearby coaching establishment (a boarding school or some sort of academy, I think). On a morning walk, Holmes meets Stackhurst who is off to the shore for a swim when they meet one of Stackhurst’s instructors, Fitzroy McPherson, who is clearly in distress. McPherson has staggered up from the beach and is barely dressed. The man appears to have been flayed, as if with a scourge. In his agony, McPherson has bit through his lower lip.

The man is soon dead, but not after uttering his last words, “the lion’s mane.” They are soon joined by another of Stackhurst’s teachers, Ian Murdoch, whom they send for the police. An investigation turns up little. Holmes believes that McPherson, whom Stackhurst was to join for a swim, never entered the water. The only other item of note is a letter found on the man, written in a woman’s hand: “I will be there, you may be sure.—Maudie.”

Although Holmes describes this case “as abstruse and unusual as any which I have faced in my long professional career,” Holmes is not without suspects. The mathematics professor, Murdoch, possesses such a terrible temper that he threw McPherson’s little dog through a plate-glass window, although Stackhurst assures Holmes that the two instructors are now “real friends.” Further, Murdoch was once rivals with McPherson for the affections of Maud Bellamy, the woman who sent McPherson the note, but again Holmes is assured that Murdoch stepped aside in favor of his friend.

Maud’s father and brother also seem likely suspects as they found McPherson’s attentions insulting. Murdoch, however, remains the popular suspect precisely because he is so unpopular (Stackhurst fires the man for insubordination), but Holmes has reasons to doubt that Murdoch could have overpowered McPherson (confusingly described as being both athletic and crippled by heart trouble) and then met Holmes and Stackhurst on the trail in the time allowed.

The mystery deepens when Holmes’ housekeeper tells him of the death of McPherson’s dog, who “died of grief” about a week after its master’s death. For Holmes, however, the discovery of the dog, found next to the pool where McPherson was to have bathed, serves to solve the mystery. He investigates the pool and remembers the dying man’s words. He returns home and consults a book that may name the murderer, and resolves to finish his investigation the next day.

But before he can set out the next day, he is joined by an inspector from the Sussex Constabulary, and it is while discussing the case that Murdoch, accompanied by Stackhurst, throws open the door to Holmes’ villa and staggers inside. On his shoulder, Murdoch bears the same injuries that led to McPherson’s death. He cries, “Brandy! Brandy!” and collapses. After treating the man, Stackhurst explains he found Murdoch stricken beside the same pool in which McPherson had intended to swim and where the dog died.

Holmes, Stackhurst and the inspector then leave for the pool and Holmes unmasks the killer, Cyanea capillata, a giant jellyfish that had been washed into the sea side pool during a recent storm. Holmes kills the creature by dislodging a rock upon it. He returns home with Stackhurst and the inspector to inform Murdoch of their discovery and inform him that he has been absolved of any guilt in the death of McPherson. Holmes also reads to them from a book that detailed a naturalist’s encounter with the jellyfish. Murdoch also confesses that he conveyed message between the two lovers.

After Murdoch and Stackhurst leave, Holmes tells the inspector that his big mistake in the case is that he had deduced that McPherson had never entered the pool for his swim because Holmes had found the man’s towel still folded and dry. He had not thought the agony caused by McPherson’s injuries would make his forgo drying off (despite the fact that McPherson was discovered shirtless and with untied shoes).

I would also add that Holmes made a further mistake by not immediately investigating the pool once he’d had his epiphany as to the identity of the murderer. As any Sherlockian knows, nothing good ever happens when Holmes delays. If he had suspicions that a giant jellyfish lurked in the pool, wasn’t it his duty to return first thing the next morning and post a sign: “Warning: Pool may contain deadly, giant jellyfish!”

I’m also puzzled by the death of the second dog. Holmes described the dog: “The body was stiff and rigid, the eyes projecting, and the limbs contorted. There was agony in every line of it.” Clearly not a dog that had succumbed to grief but one which had met a horrible end. Had the dog gone swimming in the pool as a lark? Or was it seeking revenge on the jellyfish that had killed its master? Had it, in fact, figured out the identity of the killer before Holmes?

Speaking of dogs, remember that thing I mentioned before that so infuriated me? It is, of course, the fact that Murdoch hurled McPherson’s dog through a plate glass window, an act so heinous and evil that I find it impossible McPherson could have ever forgiven Murdoch.

I cannot help but suspect that Murdoch was somehow responsible for the death of the second dog, especially as I find it unlikely the dog would have gone for a swim otherwise. With these suspicions in mind, I believe that Murdoch was trying to dispose of the incriminating evidence—the jellyfish—when he fell in the water and was stung. I think Murdoch knew of the existence of the jellyfish and may even have suggested McPherson swim in the pool. Did he throw the dog into the pool in an attempt to lure the jellyfish out? Was he unsuccessful in killing the jellyfish that day only to return the next morning? Holmes investigated the pool the day the dog died and the next morning, Murdoch is stung.

I’m sorry, a man who would throw a dog through a window is, in my mind, thoroughly evil. I do not think he stepped aside willingly to let McPherson plight his troth with Maud Bellamy but was biding his time. I am especially infuriated by these lines: “Stackhurst held out his hand. ‘Our nerves have all been at concert-pitch,’ said he. “Forgive what is past, Murdoch. We shall understand each other better in the future.’” Murdoch has duped them all.

Not one of my favorite stories. Perhaps in retrospect, I understand why Holmes chose retirement.