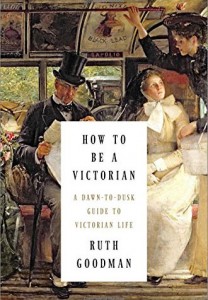

How To Be a Victorian review

Ruth Goodman is insane, but that’s good news for us because you’d have to be insane to become a freelance experiential historian. And she hadn’t become a freelance experiential historian (I term I may have made up), you wouldn’t be able to read How To Be a Victorian: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life.

Ruth Goodman is insane, but that’s good news for us because you’d have to be insane to become a freelance experiential historian. And she hadn’t become a freelance experiential historian (I term I may have made up), you wouldn’t be able to read How To Be a Victorian: A Dawn-to-Dusk Guide to Victorian Life.

Fortunately, Goodman is insane and did write this book, which looks at the lives of typical Victorians from dawn to dusk, that is from the moment of getting out of bed to going to sleep and all the moments in-between. Of course, saying typical Victorian is an almost useless descriptor. Queen Victoria reigned from 1837 to 1901, so the lives of Victorians changed immensely over that time. It included ever increasing industrialization, the railroads, telegraphs, telephones and mass migrations (the potato famine for one thing). Victorians saw the use of synthetic dyes, so their clothes became brighter; patent medicines, so they could unknowingly kill themselves; processed white flour, so they could unknowingly rob themselves of the nutritional value of wheat germ; and the Underground so that the middle class could live in the suburbs.

Goodman has a substantial challenge, for instance, talking about Victorian hairstyles because it changed so often during Victoria’s reign.

To my mind, much of the book is grim reading but what comes through clearly is that Goodman doesn’t consider it so. I don’t know that the Victorian era is Goodman’s favorite—she can be seen on many television programs living for months at a time in medieval, Tudor and Victorian millieus—but I would guess it is, if only for the creature comforts. It’s fun to read Goodman extolling the virtues of corsets, which to me sound like torture devices but to her offer necessary support for a lot of back breaking Victorian chores. She admits the original reason for corsets was the belief that women had wandering wombs and supposedly needed the support a corset gives, but her diagram of what it does to the ribcage makes one doubt its virtues.

Goodman’s book also is quite instructive in the little things that might make Victorian life more bearable. A good copper pot might make cooking easier, but a large copper pot meant you could wash your own clothes or wash the clothes of others. I especially like Goodman’s story of Tom and Kitty Wilkinson of Liverpool, who during a cholera epidemic, allowed their neighbors to wash clothing using the Wilkinson’s copper. All they asked for was a donation toward the cost of water and coal. No one knew why clean clothes helped—germ theory was in the future—but the Wilkinsons were nonetheless lauded for their selfless contribution.

Related to this were relief efforts that gave poor women a wringer or mangle, which allowed them to perform or rent out their services or machines. I like the quote she gives from the Pall Mall Gazette of 1894: “Widows and washing, misery and mangles seem, somehow, indissolubly connected.”

Schooling, of course, seems the most Dickensian of the chapters, evoking images of the Yorkshire school were Nicholas Nickleby was employed. There were, exceptions, of course, like Doctor Barnardo’s schools, where the habit of photographing new students provide a valuable snapshot of Victorian life.

Recreation is also a fun read. It’s interesting to see how the need for bath houses eventually produced large swimming pools for recreation and how football (soccer) edged out the earlier cricket because it was considered a gentleman’s sport. It’s also very interesting that some Victorian attempts to improve health still have value in the modern day. Goodman relates how she and her daughter attempted calisthenics recommended for women. Goodman, who regularly does things like churn butter, mangle clothes and dig gardens, hardly worked up a sweat doing exercises that simply looked like waving her arms around in the air. Her daughter, however, accustomed to nothing more strenuous than operating a mouse, found the exercises very tiring. The calisthenics were, of course, designed for women of privilege. The working poor generally got plenty of exercise.

How to be a Victorian is a very entertaining read and I highly recommend it. It reminds me of Jane Austen’s England in that it’s difficult to put down as the author effortlessly slides from one topic to another. I hope you’ll enjoy it as well and I hope you’ll follow Goodman on the many BBC programs in which she’s appeared. I’d hoped to post a link to the Victorian pharmacy series in which Goodman participated, but sadly those episodes have been removed from YouTube, so instead, enjoy Secrets of the Castle.