Immersing Charlotte House into the K&A Canal

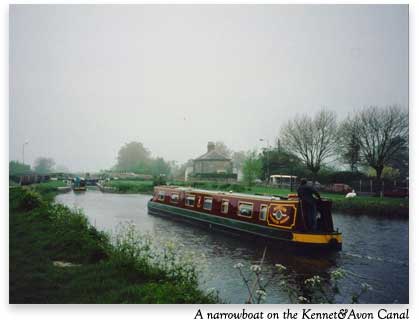

I will be visiting Bath this year with my husband Jim, my particular friend Lee and her brother Jim (much confusion I’m sure), and we’ll immediately be renting a narrowboat in Bath and traveling to Devizes on a Monday to Friday midweek trip. We’d planned this trip before I started writing My Particular Friend and although I’d already become an Austen fan, I wasn’t considering the trip for research purposes, just fun.

Since starting the book, however, I now see the trip through the eyes of someone who wants to see Austen in everything, and I became interested in any fictional Charlotte House connections with the Kennet and Avon Canal. There is, of course, Jim Shead’s excellent article for the Jane Austen Centre: Down the Kennet and Avon Canal with Jane Austen. But I was hoping that I might find pretext for a Charlotte House affair that would involve the canal, perhaps some sort of speculation scheme that would threaten a marriage.

So yes, this is again another excuse for me to wander around a topic hoping to find some kernel that I can use in one of my stories, but if you’re unfamiliar with England’s canal system, you might actually find this interesting. In the 1700s, many schemes were hatched to connect the industrial centers of England. After all, you need to get the coal you quarry to the foundries that make the iron to the ports that ship your products, and roads then were unsuitable for quickly carrying heavy loads. But England has many navigable river although they don’t conveniently join up.

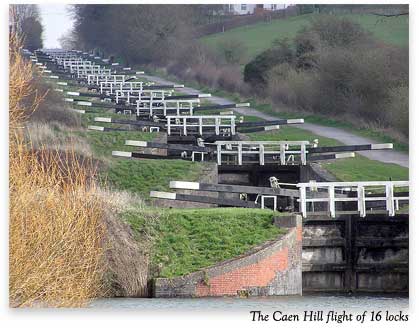

The Kennet Navigation joined Newbury to Reading in 1723 and from thence to London via the Thames, and the Avon Navigation, completed in 1727, already joined the port of Bristol with Bath. (Incidentally, this river Avon is not Shakespeare’s River Avon that does connect to Bristol via the River Severn.) But getting goods across the southern half of England meant a trip through the English Channel. The Kennet and Avon Canal Company made it possible to join Bristol directly to London and also provided the spectacle of the Caen Hill flight of 16 locks. The canal was completed in 1810 and during the Charlotte House stories Bath quarries would have been providing a lot of the stone used for bridges such as the Dundas Aqueduct and the famous Town Bridge in Bradford on Avon.

The Kennet Navigation joined Newbury to Reading in 1723 and from thence to London via the Thames, and the Avon Navigation, completed in 1727, already joined the port of Bristol with Bath. (Incidentally, this river Avon is not Shakespeare’s River Avon that does connect to Bristol via the River Severn.) But getting goods across the southern half of England meant a trip through the English Channel. The Kennet and Avon Canal Company made it possible to join Bristol directly to London and also provided the spectacle of the Caen Hill flight of 16 locks. The canal was completed in 1810 and during the Charlotte House stories Bath quarries would have been providing a lot of the stone used for bridges such as the Dundas Aqueduct and the famous Town Bridge in Bradford on Avon.

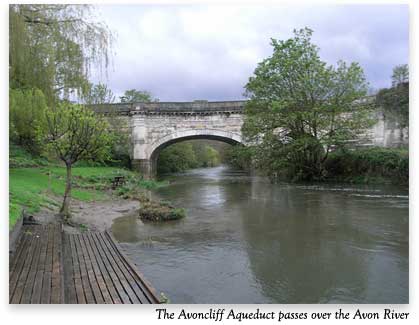

Also near Bath would be the Claverton pumping station that lifted the water that supplied the canal. The canal, after all mostly follows the path of the Avon River but is separate, which is made obvious at places such as the Avoncliff Aqueduct.

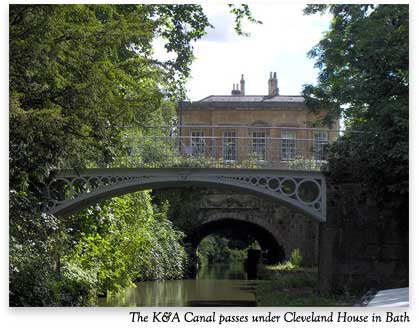

Presumably the building of the aqueduct would have introduced a whole different element — the navvies or navigation workers — who built the canals. I can’t imagine Jane Austen having much to do with this rougher sort, but Charlotte House and Jane Woodsen might have during the course of an investigation. Even Mr. Shead’s article has Austen visiting Devizes and I can well imagine Charlotte visiting Cleveland House, famous for the canal which passes underneath the former headquarters of the canal company.

Presumably the building of the aqueduct would have introduced a whole different element — the navvies or navigation workers — who built the canals. I can’t imagine Jane Austen having much to do with this rougher sort, but Charlotte House and Jane Woodsen might have during the course of an investigation. Even Mr. Shead’s article has Austen visiting Devizes and I can well imagine Charlotte visiting Cleveland House, famous for the canal which passes underneath the former headquarters of the canal company.

The canal also passes through Sydney Gardens, which has a Jane Austen connection as the gardens play a scene in Jane and the Damned.

Unfortunately the heyday of the canals was brief, quickly superseded by the other invention of the age, the steam locomotive that could move heavy goods and people even faster than the canals. The canals were almost abandoned by the 20th century although the K&A Canal was rescued when Queen Elizabeth II ceremoniously reopened it in August 1990 thanks to the hard work of volunteers and organizations such as the Kennet & Avon Canal Trust.

Unfortunately the heyday of the canals was brief, quickly superseded by the other invention of the age, the steam locomotive that could move heavy goods and people even faster than the canals. The canals were almost abandoned by the 20th century although the K&A Canal was rescued when Queen Elizabeth II ceremoniously reopened it in August 1990 thanks to the hard work of volunteers and organizations such as the Kennet & Avon Canal Trust.

Part of my desire to include the canal in a Charlotte House affair is a tribute to Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse story The Wench is Dead where, while confined in hospital because of repeated abuse of his liver, her solves a murder committed on the Oxford Canal in 1859. The story was eventually filmed and was shown in 1998 — with the K&A Canal filling in for the Oxford Canal.