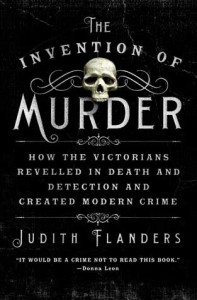

The Invention of Murder review

It’s pretty obvious while reading The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime, that it took a lot of dedication to write. It takes a lot of dedication to read, as well. There were nights I groaned when I picked it up (it is pretty heavy), but I did return to it regularly, despite the fact that it’s 556 pages long (with 89 pages of references, acknowledgements and index) with only nine chapters.

It’s pretty obvious while reading The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern Crime, that it took a lot of dedication to write. It takes a lot of dedication to read, as well. There were nights I groaned when I picked it up (it is pretty heavy), but I did return to it regularly, despite the fact that it’s 556 pages long (with 89 pages of references, acknowledgements and index) with only nine chapters.

Author Judith Flanders offers an amazing analysis of how crime captivated the Georgian, Regency and Victorian world, starting with the Ratcliffe Highway murders in London’s East End in 1811 and ending just about the time of the Jack the Ripper killings. The crimes are mostly chronological, but each chapter serves to emphasize how the crimes changed society or how society influenced crime. I found the evolution of the Metropolitan Police most interesting—from a police force that only prevented crime to the beginnings of Scotland Yard, famous for its ability to solve crime using the latest forensic techniques. I never knew that that original police force was forbidden to investigate crime, for fear of fostering a police state.

It’s also fun to see how technology served to both foster and impede crime, especially in the case of Maria Manning, who with her husband, killed Patrick O’Connor (a wealthy moneylender) and hid his body under the floor. She fled to Edinburgh by train but despite the speed and convenience of rail travel, she couldn’t outrun a telegram to Scottish authorities who apprehended her.

Flanders follows each murder from its beginning, usually outlining the crime in such a way that you’re convinced of the guilt of the accused, then to the trial where you come to doubt, then the almost inevitable execution and then to the equally inevitable play, pantomime, novels and songs that arise from the notoriety. Often these crimes had considerably staying power in the public imagination, often long after the details are forgotten. A grisly example is the expression “sweet Fanny Adams” to refer to canned meat (and later “nothing at all”). Fanny Adams was killed and her body dismembered. A law clerk was tried, found guilty and executed. In his diary, the man had written “Saturday, 24, killed a young girl; it was fine and hot.” His lawyers argued that a comma was missing and the entry should have been, “killed, a young girl,” and that the man then commented about the weather.

Blood had been found on the man’s shirt cuffs, but as there was no definitive test for blood, that was hardly definitive. Another theme running throughout the book is the very dubious nature of expert testimony. Again and again an expert would say someone showed obvious signs of arsenical poisoning (or bludgeoning with a shovel or some other means of death), only to admit they’d never actually investigated such a death. It never seemed to matter; the onus was always on the accused.

All these grisly murders and the horrible miscarriages of justice make this a hard read through no fault of the author. As a reviewer, I would have appreciated a summary of the murders and murderers to make it easier for me. We have the very early murderer Eugene Aram and poor Maria Marten from the pre-Victorian Red Barn Murder and such a long list of poisoners you’d wonder how anyone risked eating anything. Sherlock Holmes, despite being fictional and from a much later period, pops up again and again, as does Wilkie Collins, whose novels The Moonstone and The Woman in White have withered in their popularity, and yet they helped create our fascination with crime.

I highly recommend this book and I must thank my friend Mike for presenting it to me. I also recommend you watch Lucy Worsley’s A Very British Murder, because Judith Flanders is credited as an authority. Worsley’s series practically serves as a companion to Flanders’ book. Just be prepared for some sleepless nights as you keep reading, hoping for a good stopping point.